Сервис The Times Literary Supplement впервые опубликовал написанное в 1942 году стихотворение Владимира Набокова The Man of To-morrow’s Lament. Оно повествует о переживаниях Супермена из-за невозможности иметь детей с любимой женщиной — Лоис Лейн. Об этом пишет The Guardian.

Набоков отправил стихотворение редактору The New Yorker Чарльзу Пирсу. Писатель указал, что строки в середине произведения проблемные. Набоков написал, что английский язык — еще новый для него. В то время он лишь пару лет жил в США. Писатель попросил гонорар «насколько возможно адекватный для его русского прошлого и нынешних агоний».

Пирс ответил, что читатели вряд ли поймут стихотворение. Он согласился с тем, что в середине текста есть проблемы. The Man of To-morrow’s Lament так и не было опубликовано.

Литератор Андрей Бабиков нашел рукопись в папке в библиотеке Йельского университета. «Пирс и представить себе не мог, что отказ The New Yorker в публикации, возможно, первого в истории стихотворения о Супермене будет означать, что оно нигде никогда не появится. Он также не мог предвидеть, что его автор к концу 50-х станет всемирно известным писателем», — сказал эксперт.

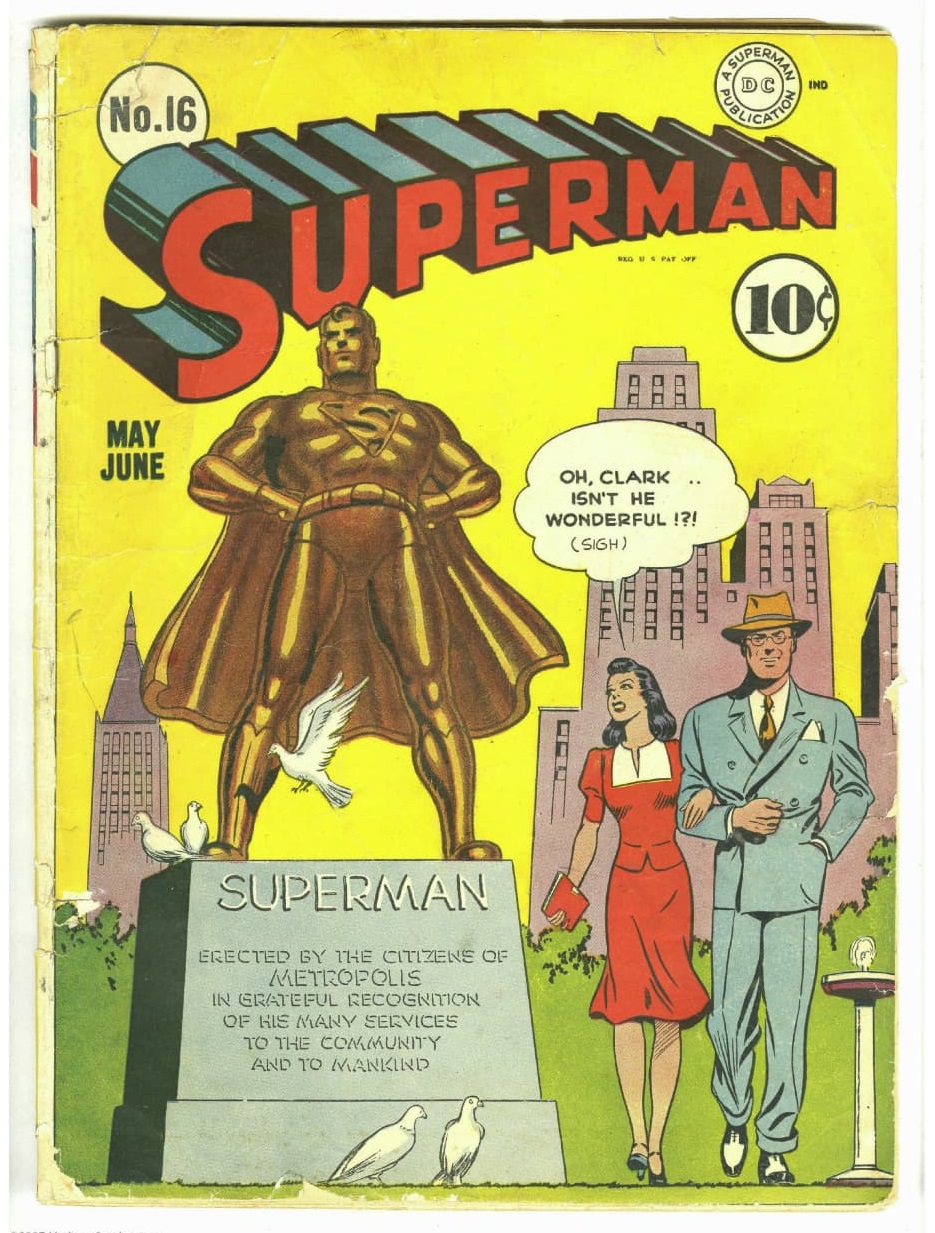

Бабиков считает, что Набокова вдохновила обложка комикса «Супермен № 16», на которой Кларк Кент и Лоис Лейн в парке смотрят на статую Супермена. Писатель даже включил в произведение фразу «Oh, Clark … Isn’t he wonderful!?!».

The Man of To-morrow’s Lament

I have to wear these glasses – otherwise,

when I caress her with my super-eyes,

her lungs and liver are too plainly seen

throbbing, like deep-sea creatures, in between

dim bones. Oh, I am sick of loitering here,

a banished trunk (like my namesake in “Lear”),

but when I switch to tights, still less I prize

my splendid torso, my tremendous thighs,

the dark-blue forelock on my narrow brow,

the heavy jaw; for I shall tell you now

my fatal limitation … not the pact

between the worlds of Fantasy and Fact

which makes me shun such an attractive spot

as Berchtesgaden, say; and also not

that little business of my draft; but worse:

a tragic misadjustment and a curse.

I’m young and bursting with prodigious sap,

and I’m in love like any healthy chap –

and I must throttle my dynamic heart

for marriage would be murder on my part,

an earthquake, wrecking on the night of nights

a woman’s life, some palmtrees, all the lights,

the big hotel, a smaller one next door

and half a dozen army trucks – or more.

But even if that blast of love should spare

her fragile frame – what children would she bear?

What monstrous babe, knocking the surgeon down,

would waddle out into the awestruck town?

When two years old he’d break the strongest chairs,

fall through the floor and terrorize the stairs;

at four, he’d dive into a well; at five,

explore a roaring furnace – and survive;

at eight, he’d ruin the longest railway line

by playing trains with real ones; and at nine,

release all my old enemies from jail,

and then I’d try to break his head – and fail.

So this is why, no matter where I fly,

red-cloaked, blue-hosed, across the yellow sky,

I feel no thrill in chasing thugs and thieves –

and gloomily broad-shouldered Kent retrieves

his coat and trousers from the garbage can

and tucks away the cloak of Superman;

and when she sighs – somewhere in Central Park

where my immense bronze statue looms – “Oh, Clark …

Isn’t he wonderful!?!”, I stare ahead

and long to be a normal guy instead.